• Research, Image by Thomas & Jurgen

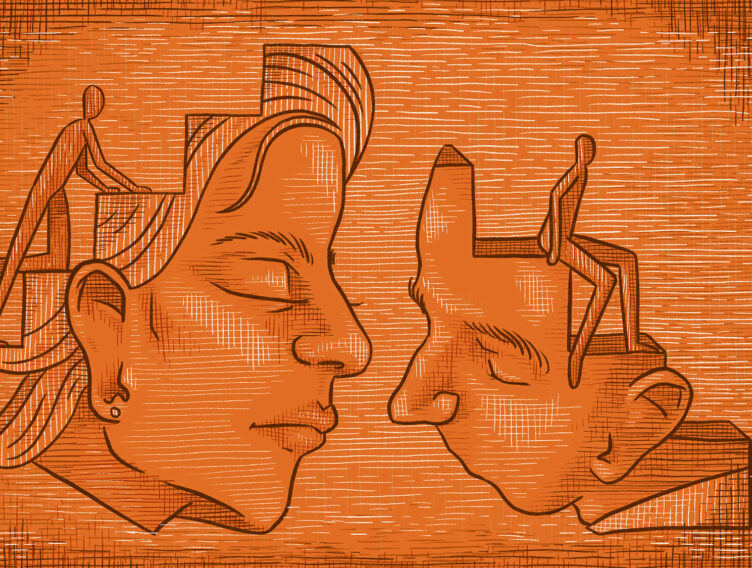

What role does research play in the design process?

In the second studio session, social designer Dorian Kingma (SMELT) talks to graphic designers Thomas Bevelander en Jurgen Wiegeraad (Thomas & Jurgen), social behaviour artist Myrte van der Molen and social designer and design researcher Myrthe Krepel (SMELT).

Dorian starts off: “During my education at Delft University of Technology, I always learned that research plays an important role in the design process. And not just any research, no, objective and systematic research, with measurable results and reliable sources. It served as evidence to support my final design. As a result, I frantically searched for sources that support my line of thought. Although I already knew what direction I wanted my design to go, I could not go anywhere without a quote from a scientific paper. At times, it made me forget my own vision. I was building an impenetrable ivory tower, instead of one that invited visitors to enter.” Myrthe K., besides her work for SMELT also a student at Delft University of Technology, recognizes the need to dive into theory at the start of each new project. Because SMELT projects deal with different social challenges every time, it is important to swiftly become an expert on the subject at hand. “I always want to read about the subject first. I have the need to gather a lot of information on the subject in order to understand how to relate to it. Only then, do I feel comfortable making something.

This is the opposite of the work routine of Thomas and Jurgen. Their research always starts with creating something. They even developed their own method, based on jazz. Jurgen: “We have a great fascination for jazz: how a group of musicians freely moves to the rhythm restricted by a set of rules. Actually our goal was to move as freely as those musicians in our visual designs. Therefore, we researched the core values of jazz improvisation and we have applied these into our own methodology.” This visual research has become increasingly important to Thomas and Jurgen to the point that they want to make it their prime centre of attention. Jurgen: “To put it crudely, at times the end product feels as the garbage left behind after an extremely interesting process. It is precisely this creative process that we enjoy sharing with the public. Because within that process, the most interesting considerations and choices reveal itself.”

According to Myrte van der M. the assignment and the presence of a client, influence the kind of research she conducts. While Thomas and Jurgen immediately start working visually, SMELT first starts with the theory, Myrte van der M. realizes that in her projects theoretical research and research into form always intertwine. According to her, the most important thing to being a maker is to always regard everything with an open mind, quite similar to a sponge. “For me, it is mostly about collecting and searching for inspiration. For example, by talking to people. Because once you are talking about the subject, someone will be likely to shine upon the matter from a different perspective.” If one thing is learned from this studio session, it is that design and research are nearly inseparable: design is research. Despite the different design disciplines, all agree that research in the design process is much more valuable when it is not about creating objective, measurable results. It is not the search for the one and only objective truth that convinces the outer world of your story. It is the gaining of inspiration, the development you go through as a designer that serves as a stepping stone for the design. A much more personal perspective on research than I was ever taught. Myrthe K.: “The vision of the designer is pivotal. If all the designers here would receive the same assignment, the same books to read and the same people to talk to, then still, we would come up with different designs. Exactly this, is what makes it interesting!”

At the same time it makes the design process less certain. At the start, it is impossible to precisely define the results and their values. A designer thrives in this: after all, they are used to processes with an uncertain outcome. Thomas: ”When something is published, we don’t know how people will respond to it. But I think this is what we consider cool, that we and the world around us can finally see the results. If it turns out to be complete rubbish, it is rubbish. If it turns out to be fantastic, it is fantastic.“ Clients and funds sometimes find this uncertainty more difficult to handle than the designers themselves. In advance, we try so hard to exert some control over the results, while in truth this is impossible to do. By devising a method, as Thomas and Jurgen have done, or by writing an extensive project plan with phases and go/no go moments, like Myrte, Myrthe and Dorian have done time and again.

Research & design process

Dorian concludes that if she would compare the research from her current design practice with that during her education, the value of research is not only found in scientific papers and carefully structured argumentations. “The methods and skills learned in education are still used, but more freely applied. That freedom is equally important for all the designers at the table. Research does not only limit itself to a book, computer, the workspace or a designer’s studio. It happens constantly and everywhere around us.” Much similar to basic principles of the method described by Thomas and Jurgen: create in the moment, find freedom in the limitation, embrace the unexpected and dare to fail. Because research is most effective when the desired outcome, answers or solutions are not determined in advance, or when we are judged accordingly.

A subtle balance is required between a designer’s freedom to follow its intuition and the limits of the project imposed by the client. Can clients embrace the unexpected? Do they dare to fail? To create this freedom, trust is required. How do you ensure that trust as a designer? And can we, as designers, find the freedom in the limits that are imposed?

Originally published by Dutch Design Week magazine.

Intrigued by this Studio Session? Listen to the full podcast here.